About

Sherpa will set off on the critical ice laden middle section of the Northwest Passage on the 26th August 2019, expecting to reach the coast of Greenland within 3 weeks if all goes according to plan.

There are seven guests and twenty-one crew.

Introduction

“The Northwest Passage” – the mere mention of the words will bring a nod of recognition and shiver down the spine of most people. Of all the great ocean routes it is probably the most recognized and most feared. Why?

Because no maritime route had obsessed man for so long without success, the great names of exploration have left their mark in perpetuity; Davis Strait, Baffin Island, Frobisher Bay, Hudson Bay, Foxe Basin, James Bay – the list goes on and on; Ross, Franklin, Cook. They all tried and failed, often at enormous cost; lives lost, fortunes expended. Films have been made about it, songs have been written about it, scores of books have sought to explain and capture the passion and fear that it continues to generate.

The sheer remoteness and the potentially deadly weather have meant that of all the great maritime endeavours it remains one of the most dangerous. Even today as modern technology and climate change have permitted the occasional transit, it remains a capricious and risky element of Mother Nature’s portfolio. Over four thousand people have climbed Mount Everest, yet less than 300 boats have ever transited the Northwest Passage.

At the end of her NW Passage, MY Sherpa will be recorded in the Scott Polar Research Institute as one of less than 300 vessels to have ever completed the NW Passage.

Modern Day

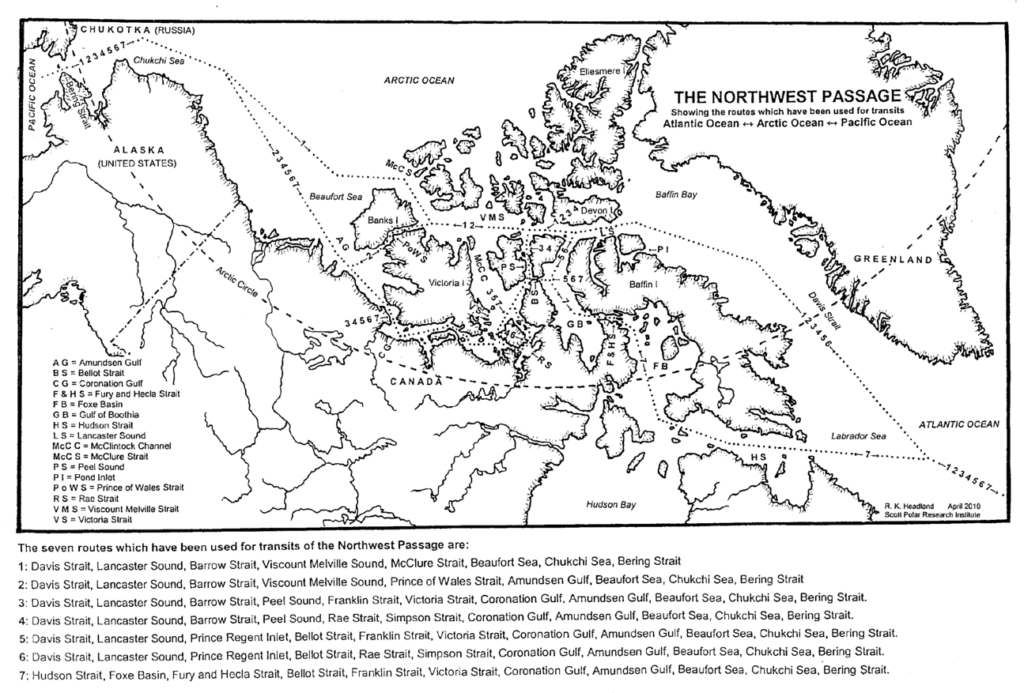

To the end of the 2018 navigation season, 290 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland.

Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1).

Ice

Measurements of the polar ice cap shows a marked reduction in the summer sea ice cover. The sea ice minimum has been occurring later in recent years due to a longer melting season. In some areas, sea ice will be forming whilst at the same time, ice will be shrinking in other areas. Although the area of sea ice in the winter remains similar to that recorded 10 years ago, much of the ice is new ice formed within the last 12 months. This is much thinner than multiyear ice found in the past but still pose a real danger to vessels.

Even though the ice pack in general is diminishing, depending on winds, currents and surrounding land masses, any existing remaining ice may still create a total barrier. Passage through ice of apparently passable density, such as 3/10, is often obstructed where the ice is gathered into areas of greater density. Peel Sound, Navy Board Inlet and Bellot Strait are particularly susceptible to becoming blocked when prevailing winds force pack ice into these bottle necks.

At sea, two basic types of ice are encountered:

1. Icebergs – calve of glaciers, originate on land and consist of freshwater. Icebergs are classified by both their shape and size (Shape – Tabular, Domed, Pinnacle, Wedge, Dry Dock, Blocky) (Size – Growler, Bergy, Small, Medium, Large and Very Large)

2. Sea Ice – frozen seawater which forms, melts and grows in the ocean. Sea ice is classified by age and forms (Age – New Ice, Nilas 10cm, Young Ice 10-30cm, First Year 0.3 – 2m, Multi-year 2m+) (Forms – Pancake, Brash, Cake, Floe, Fast)

People and Culture

The Alaskan and Canadian Arctic were first populated by nomadic Inuit people from Siberia. This migration occurred in the last ice age and the people were known as Yup’ik Inuit, Alutiq and Athapaskans. They had extensive trade and cultural networks from Greenland to Siberia and southwards as far as Korea, Japan and China.

The word Eskimo means eaters of raw meat and although it is widely used outside of the Arctic, most indigenous people in Greenland and Canada prefer the term Inuit which means the people. Calling someone an Eskimo can be considered to be offensive.

The existence of the Inuit people is dependent on hunting caribou, fish and sea mammals. The northern communities specialise in hunting bowhead whales, walrus, seals and polar bears and the southern communities on caribou and seals.

Kinship and hunting lie at the core of Inuit community life. In Inuit culture, one’s close kin is not necessarily biologically related. For example, two men who hunt together form a close bond and might regard each other as kin.

In both Canada and Alaska, government policy has been to resettle Inuit in settlements. Although hunting is still very important, some settlements now have supermarkets stocked with the worst of convenience foods.

As of the 2006 Canada Census there were 4,165 Inuit living in the Northwest Territories.

*Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics

Arctic Wildlife

It is hard to believe that such a harsh and barren environment can harbour any wildlife however surprisingly, a number of species have adapted to the cold conditions and has become masters at survival. We hope to encounter a few of these along our passage.

Marine Mammals

Various types of seals can be found in the Arctic:

Harbour or Common Seal – they grow to 1.85m and weigh up to 130kg

Ringed Seal – commonly encountered seal which can be found year round

Harp Seal – medium sized with distinctive harp shaped markings

Bearded Seal – large seal that can grow up to 3m and 420kg

Hooded Seal – large seal that can grow up to 2.6m and 400kg

Walrus – very large seal that can grow up to 3.4m and 1,350kg

Whales

Bowhead Whale – known to old commercial fisherman as the ‘Right Whale’ because it was relatively easy to hunt and did not sink once killed. Grows up to 18m long.

Fin Whale – large whale that grows up to 24m long and is an endangered specie.

Lesser Rorqual -a smaller thin whale found in the eastern waters of the NW Passage. They can grow up to 6m long.

Blue Whale – the largest of all mammals and can grow to over 30m in length. It is also an endangered specie.

Humpback Whale – commonly found throughout the NW Passage and can grow up to 16m in length.

Beluga Whale – a small whale that can grow up to 4m in lenght.

Narwhale – seen along the eastern shores of the Arctic and can grow up to 4.5m in length.

Killer Whale – actually part of the porpoise family. They can grow up to 7m in length.

Fish

A number of freshwater fish survive beneath the ice in inland lakes and rivers.

At sea, the following fish can be found:

Cod – weight less than 2kg

Lamphrey – eel like creature with no jaw

Arctic Char – similar to salmon

Dolly Varden – similar to salmon

Sculpin – ugly non-edible fish

Halibut – not very common

Capelin – small silvery fish which live in deep water

Small Land Mammals

Shrews, voles and lemmings are important creatures in the food chain providing food for larger mammals.

Arctic Hare – largest type of hare and are often a pure white colour.

Arctic Ground Squirrel – lives in the tundra on vegetation and scavenged meat.

Larger Mammals

Polar Bears – synonymous with the Arctic, they can be found throughout the NW Passage. They can grow up to 700kg, swim at an average speed of 6kts and run up to 40km/h.

Wolves – pure white in colour, travel in packs and hunt large game such as caribou.

Arctic Fox – mostly eat voles and lemmings but will scavenge larger carrion.

Wolverines – A type of weasel that grows to the size of bear cubs. They are an endangered specie.

Caribou – a member of the deer family, an important food source to both man and predator mammals.

Moose – largest of the deer family.

Musk-ox – can weigh up to 450kg and run up to 60km/h.

Birds

Most Arctic birds are migratory however the snowy owl, rock ptarmigan, gyrfalcon and raven are resident species.

Routes

Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (transits 149 and 167). These are shown on the map following, and proceed as follows:

1: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, Viscount Melville Sound, McClure Strait, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. The shortest and deepest, but difficult and northernmost, way owing to the severe ice of McClure Strait. The route is preferred by submarines because of its depth.

2: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, Viscount Melville Sound, Prince of Wales Strait, Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. An easier variant of route 1 which may avoid severe ice in McClure Strait. It is suitable for deep draft vessels.

3: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, Peel Sound, Franklin Strait, Victoria Strait, Coronation Gulf, Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. The principal route; used by most larger vessels of draft less than 14 m.

4: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, Peel Sound, Rae Strait, Simpson Strait, Coronation Gulf, Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. A variant of route 3 for smaller vessels if ice from McClintock Channel has blocked Victoria Strait. Simpson Strait is only 6·4 m deep, it has shoals and complex currents.

5: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Prince Regent Inlet, Bellot Strait, Franklin Strait, Victoria Strait, Coronation Gulf, Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. This route is dependent on ice in Bellot Strait which has complex currents. Mainly used by eastbound vessels.

6: Davis Strait, Lancaster Sound, Prince Regent Inlet, Bellot Strait, Rae Strait, Simpson Strait, Coronation Gulf, Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. A variant of route 5 for smaller vessels if ice from McClintock Channel has blocked Victoria Strait. Simpson Strait is only 6·4 m deep, complex currents run in it and in Bellot Strait.

7: Hudson Strait, Foxe Basin, Fury and Hecla Strait, Bellot Strait, Franklin Strait, Victoria Strait, Coronation Gulf, Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Strait. A difficult route owing to severe ice usually at the west of Fury and Hecla Strait and the currents of Bellot Strait. Mainly used by eastbound vessels as an alternative

is practicable.

Complete transits have been made by 222 different vessels. The Russian icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov has made 18 transits, the largest number of any vessel. Hanseatic has made 11, Bremen 9 (2 with the former name, Frontier Spirit), Polar Bound 7; 3 vessels have each made 3 transits, and 21 have made 2. More than one year was taken by 31 of these vessels, mainly small craft, to complete a transit wintering at various places along the route (complements of some of these vessels left for winter returning in a later navigation season). Return transits in one summer have been made by 5 vessels.

An analysis of the transit routes used through the Northwest Passage to the end of navigation in 2018 shows:

Route | East to West | West to East | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

Route 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Route 2 | 13 | 4 | 17 |

Route 3 | 40 | 30 | 70 |

Route 4 | 45 | 11 | 56 |

Route 5 | 22 | 36 | 58 |

Route 6 | 34 | 42 | 76 |

Route 7 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

Composite | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Total | 159 | 131 | 290 |

History

It is perhaps best known for the ill fated expedition led by Sir John Franklin in 1845 when he and all of his men perished without trace. Whilst many vessels and men have been lost in the course of discovery, the fact that such a well prepared expedition foundered with the loss of all hands and the subsequent allegations of cannibalism by local Inuit raised the notoriety of the Northwest Passage to fearsome levels. What could drive men not only to endure such extreme hardship, but to break one of humanity’s greatest taboos in the process?

In simple terms it was the desire to be the first to find a way through. From the moment that Columbus had discovered the Americas, it became a political and economic imperative to find a way through to the riches of Asia. Whilst Magellan had found his eponymous strait in the south of America in 1520, it was the long way round and a shorter route had the potential to deliver untold wealth and power for those who discovered and controlled it. Furthermore it offered the chance to profit from the burgeoning fur trade in the vast Canadian provinces. The first recorded expedition was in 1497 when Henry VII sent John Cabot to explore from the East.

Attempts were also made to find a route from the Pacific. The Spanish referred to the Northwest Passage as the “Straight of Anian”. In 1539 the Spanish explorer Francisco de Ulloa set sail from Acapulco in search of a Pacific route. He didn’t get very far and turned around in the Gulf of California when he was unable to find the fabled Strait of Anian – though a cursory analysis of the navigation shows that he was some way off his target!

Attempts from the UK continued and in 1631 Luke Foxe and Thomas James left on an unsuccessful search for a way beyond Hudson’s Bay and it was not until 1668 that another vessel from Europe attempted to enter the Hudson’s Bay. The voyage of the “Nonsuch” was largely a commercial enterprise to obtain furs from the local Cree Indians and when the ketch returned to England it was with the news that ‘Beaver is very plenty’. In 1670 the Hudson’s Bay Company was established by Royal Charter to exploit this new-found trade and was given a monopoly over the seas, straits and lands within the entrance of the Hudson Strait. Whilst the company had little interest in the Northwest Passage, it’s establishment of trading posts encourage the explorers that perhaps conditions were not as hazardous and within a few decades a fresh enthusiasm had resumed that a way might be found through.

It was ironic that so many attempts to find the Northwest Passage took place in the so called “Age of Enlightenment”or “Age of Reason”, when many took a determined attempt to dispel myth and ignorance with a more dispassionate and rational approach to science and society because that was precisely the quality lacking in so many voyages; they were founded on blind faith and little more.

After James Knight’s disastrous expedition of 1719 it was another 12 years before it found a new champion in the form of Arthur Dobbs, a newly elected Irish MP who published a 70 page ‘Memorial’ in which he argued

“What great advantages might be made by having a passage to California in three or four months & so down to the Western Coast of America in the South Sea”.

Sadly his passion was not reciprocated by the Hudson’s Bay Company but Dobbs persisted and eventually the Admiralty gave orders to Christopher Middleton to search for ‘a strait or an open sea’ to the west. On 8th June 1741 the Furnace and the Discovery weighed anchor bound for Hudson’s Bay. It was not to be a successful voyage, plagued by illness and scurvy which depleted the crew the ships returned to England over a year later only to be accused of deliberately concealing a passage.

There was much at stake and with emotions running high, facts were often obscured or ignored as those such as Dobbs strived incessantly to find a way through the Northwest Passage.

Many of the great navigators and explorers tried, James Cook sailed in July 1776 from Plymouth on what was to be his final voyage ‘to take possession in the name of the King of Great Britain, of convenient situations in such countries as you discover’. After sailing into the Pacific, he made good progress into the Beaufort Sea but faced by a wall of ice, he returned to Hawaii for the winter where after a initial warm reception, matters turned for the worse when having put to sea but forced to return to make repairs, Cook was killed in a minor skirmish.

The search for the Northwest Passage is intertwined with other notable Arctic adventures. John Barrow, an ambitious civil servant had been appointed Second Secretary at the Admiralty and was obsessed with finding a route through. Around 1815 he persuaded the Royal Society to set a sliding scale of rewards for Arctic exploration. Ranging from £5,000 for the first vessel to reach 110’W, to a jackpot of £20,000 for discovering the Northwest Passage. Supported by the Admiralty, two expeditions set off in 1818: John Ross on the Isabella was charged with finding a passage to the Pacific, whilst John Franklin was to lead the Trent towards the North Pole. Both expeditions could hardly be described as wildly successful and in Ross’s case caused him to fall out of favour with Barrow and the Admiralty. Undeterred he persuaded Felix Booth, the gin distiller, to fund an expedition back to the Arctic, where he rewarded his sponsor by naming the Boothia Peninsula after him – still the only peninsula named after a brand of Gin!

Sir John Franklin is synonymous with the search for the Northwest Passage, he made his first Arctic voyage on the Trent in 1818 where he was commended by his commanding officer for his “zeal and alacrity”. Imbued with enthusiasm he commanded an overland expedition from 1819 to 1822 which despite the loss of half the party established his credential as a Polar explorer and more popularly as “the Man who ate his boots”, a situation forced upon him by lack of food but which ultimately burnished his reputation in the eyes of the British public and the Admiralty.

As a consequence he was chosen to lead the well prepared expedition of the Erebus and the Terror in 1845, perhaps the most famous and infamous of all Northwest Passage trips. The ships were refitted to cope with ice and the cold and departed England with three years of provisions, including the latest canned food. Both ships disappeared with all hands and no explanation as to what happened to them. Despite repeated rescue attempts, including one funded by Franklin’s wife, precious little is known about their demise. The recent discovery of the two ships has still yielded scant information about what caused their demise; was it scurvy? was it lead poisoning from the canned food? was it starvation? Did they resort to cannibalism in an effort to survive?

In 1853 it was his potential rescuer Robert McClure and his crew and in turn those of McClure’s rescuer, Sir Edward Belcher, who became the first men who could claim to have traversed the Northwest Passage, albeit partially by land as McClure approached from the Pacific but was rescued by Belcher’s party who had come from the Atlantic.

What remains fascinating are the risks that the rescuers took to try and find Franklin and his men. McClure was sent on his rescue mission five years after Franklin’s departure but had to wait another 3 winters in the ice before Belcher’s rescue mission found them. It is difficult to comprehend the privation and suffering that all parties endured. Franklin’s wife, Jane, was still convinced that her husband was alive. In 1857 she bought a steam yacht, The Fox, and charged Leopold McClintock with continuing the search. Despite concluding that all had perished, his discovery of further artifacts and evidence that Franklin had died in 1847 went a long way to rehabilitating the reputation of the brave explorers.

It was to be over a half century later that Man triumphed over nature and it befell one of history’s greatest explorers, Roald Amundsen, to actually traverse the passage by boat. Typically Amundsen had learnt from previous failed attempts and chose a small sloop crewed by only six men to make his attempt. He wanted to stay close to the shore and where possible live off the land and sea. He left Oslo in 1903 and reached the Boothia Peninsula by September where the Goja remained iced in for two years in a harbour on King William Island. His crew used their time usefully learning local skills and determining the position of the magnetic north pole. His route followed the Rae Strait but it was very shallow and was not navigable by larger vessels, thus would never be a commercially viable passage. As one might expect of the great man, upon completion of the Northwest Passage element, he skied from Herschel Island to Eagle, Alaska to send a telegram announcing his success before skiing back to the Goja and his crewmates – quite some chap!!

The genie was finally out of the bottle, the Northwest Passage did indeed exist, but it would not be until 1940 when the second successful passage would occur. This time it was the St Roch, a Royal Canadian Mounted Police ice strengthened schooner that left Vancouver on 23rd June 1940 and arrived in Halifax on the 11th October 1942.

Northwest passengers needed to be patient!

Even today the Northwest Passage remains the great challenge that it has been for 500 years, a small and varied collection of ships and yachts have successfully transited, from the converted lifeboat of David Scott-Cowper to the ice class tanker, the Manhattan, that became the first commercial vessel to pass through in 1969. More remarkably the Passage is slowly revealing some of it secrets, the discovery of the Erebus in 2014 and the Terror in 2016 has helped to explain some of that ill fated voyage whilst rekindling a fascination with this remarkable waterway.

The eternal constant is that passage is not guaranteed, Mother Nature is in charge. To transit the Northwest Passage is a privilege granted to the very few who prepare well and respect the elements, and ultimately you need a bit of luck!